For 6 days in 1977, Black lawmakers in South Carolina ground the legislative process to a halt. Their goal: to stop the death penalty from returning to our state.

These House representatives correctly predicted that, if the practice of execution were allowed to resume, the state would once again apply the penalty arbitrarily and disproportionately against Black South Carolinians.

“When you pull that switch today on your desks, it is just like pulling the switch to turn on the juice in the electric chair,” warned Rep. I.S. Leevy Johnson of Richland County, chairman of the Black Caucus.

The 6-day filibuster of May through June 1977 is not well remembered today. Even at the time, it was dismissed by some lawmakers, who practiced needlepoint, slept in their chairs, and blew bubblegum bubbles to express their boredom with the process.

On this World Day Against the Death Penalty, we want to highlight this historic all-out effort to stop the state from killing in our name. This year our state finds itself in a renaissance of violence after lawmakers passed bills authorizing the Department of Corrections to clandestinely obtain poison, assemble a firing squad, and prepare the electric chair once again.

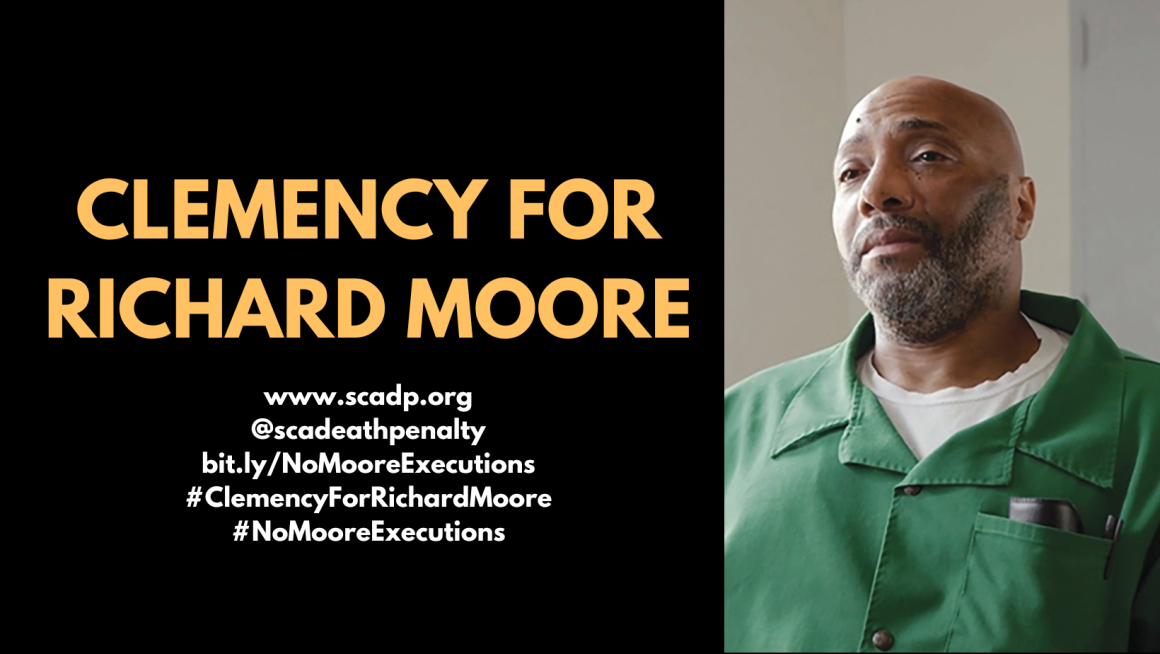

We share this history because the fight to end the death penalty continues, and we need to revive the sense of urgency that so many people felt in ‘77. If you would like to join this effort, please follow our partners at South Carolinians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty. Their website has resources including a clemency campaign for Richard Moore, who the state is set to kill on Nov. 1, and upcoming events including Journey of Hope speaking engagements across the state.

A familiar fight

“A small bloc of black House members, whose racial brothers have died in the state’s electric chair in greater numbers than any other class, launched a determined effort in the House Tuesday to try to block passage of a new death penalty law,” The State newspaper's governmental affairs reporter wrote after the first day of the filibuster on May 24, 1977.

Many aspects of the 1977 debate will sound familiar, but South Carolina’s political landscape looked different. Democrats held a supermajority in both legislative chambers, and a coalition of white Republicans quietly joined with their Black Democratic colleagues to keep the filibuster going.

Democratic Rep. Theo W. Mitchell of Greenville, a member of the Black Caucus and the ACLU of South Carolina, led the first day of the filibuster with a slow, deliberate recitation of the names of the 241 people — mostly Black men — whom the state had killed by electrocution since 1912.

“How can I be asked to discuss the merits of something that would take the life of my brother?” Mitchell asked, as dozens of Black ministers watched from the visitors’ gallery,

Rep. Mitchell called his colleagues out on their claims that the death penalty would have a deterrent effect on violent crime (it did not and does not). He accused prosecutors of trying to build their political careers on executions — a fact that remains eerily relevant in the case of Richard Moore, who received a death sentence in part due to political pressure on then-Solicitor Trey Gowdy of Spartanburg County.

Then, as now, proponents of the death penalty pointed to extreme cases of violence to make the case for killing those accused of lesser crimes. The sensational trial of serial killer Donald “Pee Wee” Gaskins was ongoing as the legislature debated the death penalty in 1977, and The State’s editorial board — led in part by the segregationist William D. Workman Jr. — pointed to Gaskins as a clear case for the death penalty, arguing that “the past was a long time ago” and Black defendants would be treated fairly going forward.

The white Democratic majority invoked cloture and broke the filibuster on Thursday, June 2, 1977. The state has killed 44 men since then. Thirty-one people remain on Death Row today, nearly half of them Black.

A question of conscience

In 1977, the entire United States had just taken a decade-long break from executions after the 1967 Supreme Court case Furman v. Georgia reduced all death sentences to life imprisonment. The 1976 case Gregg v. Georgia allowed states to give death sentences again, provided they made some amendments to their laws.

The purpose of South Carolina Senate Bill 218 in 1977 was to amend the law and resume killing.

South Carolina just had an even longer interlude, with the expiration of lethal injection drugs forcing the state to pause executions from 2011 until 2024. When the state killed Khalil Divine Black Sun Allah on September 20, it was the state’s first execution in 13 years and 4 months.

The coalition of South Carolinians who oppose the death penalty today includes people who do not see eye to eye on other issues. This year, we at the ACLU of South Carolina have been proud to stand shoulder to shoulder with the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston, Democrats for Life of South Carolina, the South Carolina NAACP, and faith leaders from a broad range of traditions who seek to end the death penalty for moral, spiritual, philosophical, or constitutional reasons.

In quieter conversations, we have begun to hear from social conservatives who do not think the government should have the power to take a life. This, too, is a familiar story from 1977.

“Lawmaker’s Decision Didn’t Come Easy,” read a headline on May 26, 1977, on page 5-B of The State. The reporter described Rep. Robert N. McLellan Sr., a 52-year-old insurance agent from Oconee, as a contemplative, conservative elder in a Presbyterian church who believed in crime and punishment. As the House considered the death penalty, his conscience was troubled.

“I’ve got a moral which I’m reluctant to discuss. It’s a feeling that since I’m not permitted to give life, I shouldn’t take it,” McLellan said.

McLellan described how he carefully weighed the evidence. Before he could vote to resume executions, he said, he needed to be convinced that executions would deter crime. But the evidence wasn’t there.

He could not vote for the death penalty “because it does not do what they represent it to do,” he said.

“If I could, I would override my moral feelings about it,” McLellan confessed. But he could not override them, and so he took a stand.

Sign the Petition: Stop the Execution of Richard Moore in South Carolina