Democracy doesn’t just happen. It doesn’t fall from the sky or spring up from the soil. We the people have to protect and advance it.

Earlier this month, the ACLU of South Carolina was proud to play its part in the ongoing struggle for democracy in our state. On August 11, as part of a legal team including the ACLU, the Legal Defense Fund, and Arnold & Porter, we filed our brief in Alexander v. South Carolina NAACP. The case is set to be the most consequential racial gerrymandering case of the decade.

On Oct. 11, the Supreme Court of the United States will hear oral arguments in our case. If the Court affirms our trial victory from last year, South Carolina will be forced to redraw its Congressional districts more fairly. As we prepare to go to court, we’d like to catch you up on the case and what its outcome will mean for all South Carolinians.

One of the plaintiffs we represent in this case is Taiwan Scott, a seventh-generation resident of Hilton Head and member of the Gullah community. When we filed our brief with the Supreme Court earlier this month, he summed up the case this way:

The configuration of my current congressional district—CD1—represents a continuation of majority white legislative bodies seeking to minimize Black voters’ electoral power and the full promise of equal citizenship for Black people in my community. A panel of federal judges has already ruled once that we are entitled to a fair map, and I am hopeful that the Supreme Court will affirm the panel’s decision and remind South Carolina that my community has the same constitutional rights to equal and fair representation as our non-racially gerrymandered neighbors.

The case

This case, originally called South Carolina NAACP v. Alexander, is about the redrawing of electoral maps in South Carolina. Every time there is a census (every 10 years), state lawmakers must redraw electoral districts to ensure that each includes the same number of voters. In South Carolina, the process is often deeply fraught. In 4 of the last 5 redistricting cycles, federal court intervention was necessary to ensure our maps were compliant with the law and the protections of the Constitution.

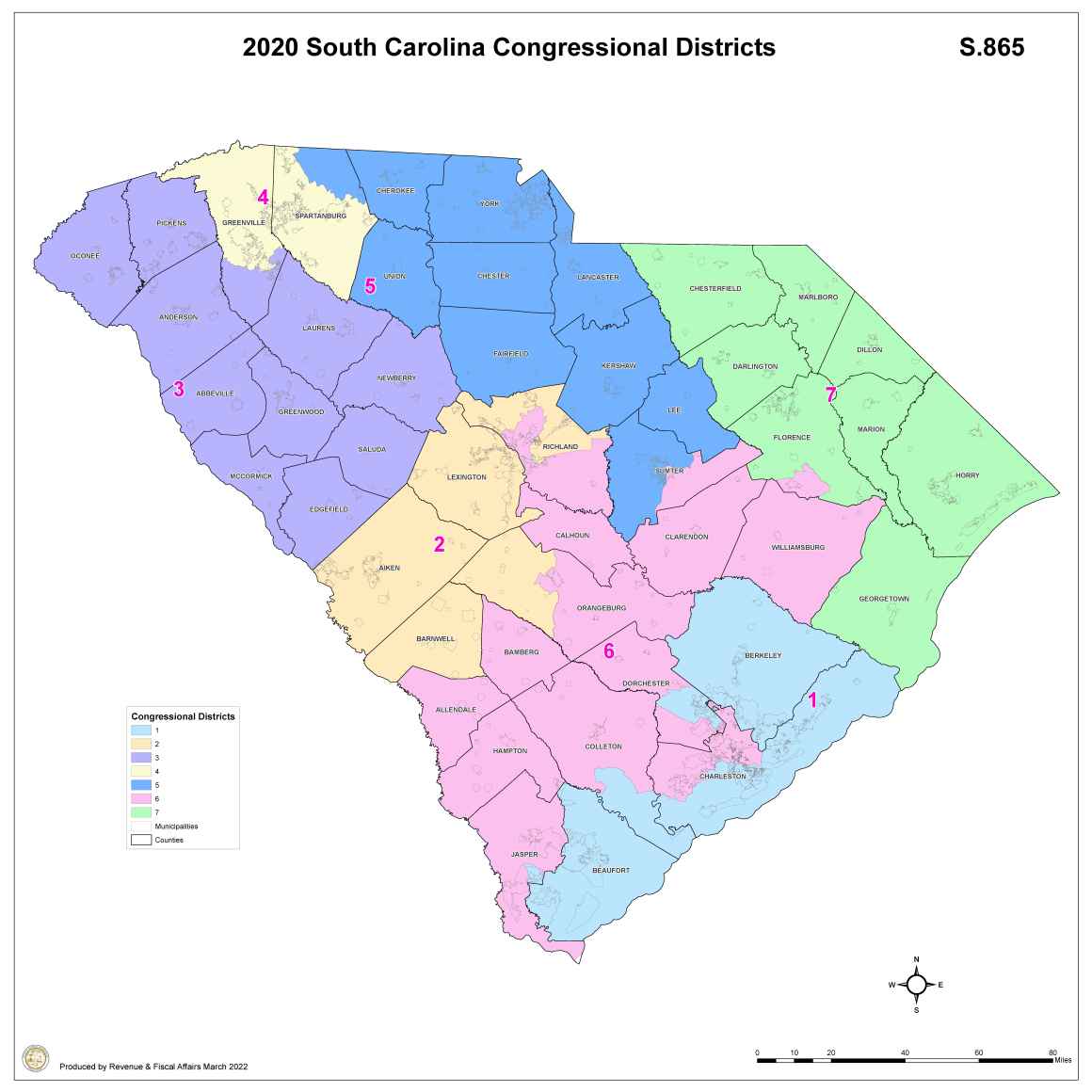

Our case before the Supreme Court focuses on two Congressional Districts: District 1, a Charleston-area district currently represented by Rep. Nancy Mace, and District 6, a sprawling district reaching from Columbia to Charleston that is currently represented by Rep. Jim Clyburn.

We went to an 8-day trial featuring 652 exhibits and testimony from 42 witnesses. We were able to show that mapmakers disregarded traditional redistricting principles and sorted thousands of voters on the basis of race. Furthermore, despite lawmakers telling the public throughout the redistricting process they were not going to politically gerrymander (that is, intentionally manipulate the district lines to benefit Republican politicians), they testified in court that they had done just that.

Our plaintiffs won their case. In January 2023, a panel of three federal judges found that lawmakers had “bleached” Black voters out of District 1 and made a “mockery” of traditional districting principles. The judges found that lawmakers had illegally manipulated racial demographics in District 1 in order to shore up a 6-1 Republican majority in South Carolina’s congressional delegation.

The judges ordered South Carolina lawmakers to redraw their maps, writing at the time:

Reducing the African American population in Charleston County so low as to bring the overall black percentage in Congressional District No. 1 down to the 17% target was no easy task and was effectively impossible without the gerrymandering of the African American population of Charleston County.

The defendants, including Senate President Thomas Alexander, appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of the United States. This brings us to our upcoming court date in October.

The evidence

We’re legal nerds here, and we know court filings are not always a riveting read, but our brief to SCOTUS has some details that should raise real concerns about the state of our democracy. You can read it all on the Cases page on our website or look around in the other filings at supremecourt.gov.

For example, we show that South Carolina’s lawmakers “offset virtually every Black voter added to CD1 from Beaufort, Berkeley, and Dorchester by expelling a Black Charlestonian from CD1 to CD6.” Majority-Black communities in Charleston and North Charleston were pushed out of District 1, separating them from majority-white parts of the county and the coast.

We include evidence presented by Dr. Kosuke Imai, a statistician who used algorithms to generate alternative maps of the two districts based on traditional redistricting principles while ignoring racial data. After running the numbers, he testified that the low Black population in District 1 was “astronomically” unlikely to occur if, as the defendants claim, the map drawers never considered race.

There’s also some interesting reading in the amici curiae, or “friend of the court” briefs on this case. These are statements submitted by people who are not parties to the case but want to lend some expertise or perspective.

Consider the opening paragraph of the amicus brief from the League of Women Voters of South Carolina, Gullah Geechee Chamber of Commerce, Charleston Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, and Circular Congregational Church:

Fifty-five million years ago, the Atlantic Ocean and South Carolina’s coast converged in the Midlands, more than one-hundred miles from the state’s modern-day shoreline. Not since that time has Columbia held interests resembling those of Charleston County. Nevertheless, in 2021, the South Carolina General Assembly needlessly deepened the split of Charleston County between Congressional District Nos. 1 and 6 and, for the first time ever, lumped together in a single district the whole of the Charleston Peninsula and downtown Columbia, which are separated by several rural counties and more than half the state’s length. The General Assembly’s fragmentation of Charleston County and amalgamation of communities with disparate interests typify the Enacted Plan’s disregard for traditional redistricting principles and demonstrate the predomination of race as the General Assembly’s primary redistricting consideration.

That is, if nothing else, some good writing.

Why we fight

Beneath the legalese and the mountains of paperwork in this case, you’ll find some bedrock principles of American life: that one person should have one vote; that every person is deserving of equal protection under the law; that voters should choose their representatives and not the other way around.

These are enduring ideals that transcend party lines. In fact, if you look at the long history of redistricting challenges in South Carolina, it was the South Carolina Republican Party that fought for fairer districts in 1984, alongside the NAACP. Again and again, regardless of who held power and who stood to gain, people of principle have stood in the gap for the sake of democracy.

As ACLU founding member Helen Keller once said, “Rights are things we get when we are strong enough to make good our claim on them.” After more than a century in existence, the ACLU is still striving to make voting rights real and lasting in the United States. Working arm in arm with partners like the NAACP and LDF, we aim to protect the ballot and the rights of South Carolinians. We want a democracy, and we’re willing to fight for it.